A Surprising Dinner Party

EM Forster visits America

The story of this quote--slightly changed from the original--

appears in the Preface for Johnson's novel Secret Matter

Toby Johnson submitted a Letter to the Editor regarding a mention of Joseph Campbell in a story about George Platt Lynes.

In

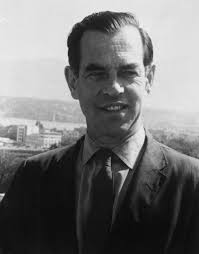

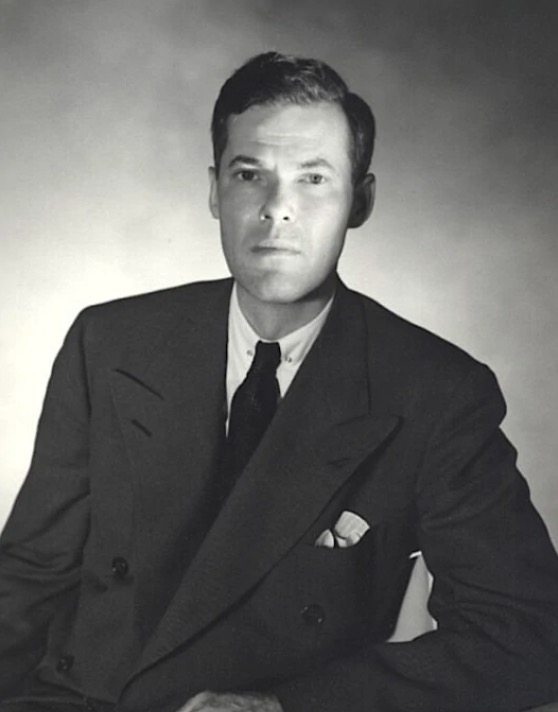

a Letter to the Editor in the July-August issue, Michael Bedwell tells

of a 1949 literary gathering for novelist E.M. Forster (shown right at

about age 35) who was visiting America, hosted by New York socialites,

publisher Monroe Wheeler and his lover Glenway Wescott whose 1971 NY

Times article is the source of this information. Photographer George

Platt Lynes, with his mother Adelaide, came for cocktails to meet

Forster and his “friend of long standing” Bob Buckingham and arrange to

photograph them later in the week. At the dinner party after the

Lyneses left were the two hosts; Forster (age 70) and Buckingham; and

two more, perhaps incongruous, guests: sexologist Alfred C. Kinsey and

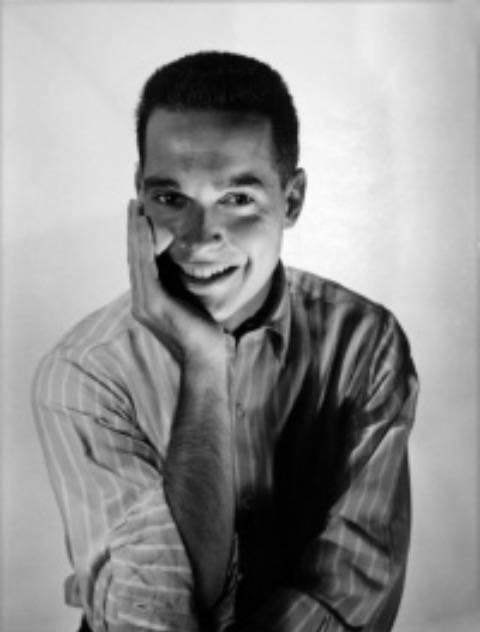

comparative religions scholar Joseph Campbell (age 45 -- the photo

below looks mid-40s).

In

a Letter to the Editor in the July-August issue, Michael Bedwell tells

of a 1949 literary gathering for novelist E.M. Forster (shown right at

about age 35) who was visiting America, hosted by New York socialites,

publisher Monroe Wheeler and his lover Glenway Wescott whose 1971 NY

Times article is the source of this information. Photographer George

Platt Lynes, with his mother Adelaide, came for cocktails to meet

Forster and his “friend of long standing” Bob Buckingham and arrange to

photograph them later in the week. At the dinner party after the

Lyneses left were the two hosts; Forster (age 70) and Buckingham; and

two more, perhaps incongruous, guests: sexologist Alfred C. Kinsey and

comparative religions scholar Joseph Campbell (age 45 -- the photo

below looks mid-40s).

I

was intrigued that Campbell had been invited. The reason, of course,

was the subject matter: Forster was the celebrated author of A Passage

to India and Campbell an Indiologist and Sanskrit scholar. This dinner

sounds like a fairly gay event. I am always happy to learn evidence of

Campbell’s open-mindedness in this regard—and at a time (1949) when

open-mindedness wouldn’t have been the norm. Campbell himself was not

gay; his first real girlfriend, btw, was Adelle Davis, later the health

food maven and inventor of tiger’s milk, and he was famously married to

Broadway choreographer Jean Erdman.

I

was intrigued that Campbell had been invited. The reason, of course,

was the subject matter: Forster was the celebrated author of A Passage

to India and Campbell an Indiologist and Sanskrit scholar. This dinner

sounds like a fairly gay event. I am always happy to learn evidence of

Campbell’s open-mindedness in this regard—and at a time (1949) when

open-mindedness wouldn’t have been the norm. Campbell himself was not

gay; his first real girlfriend, btw, was Adelle Davis, later the health

food maven and inventor of tiger’s milk, and he was famously married to

Broadway choreographer Jean Erdman.

Gracious

and open-minded—that’s how I experienced Joseph Campbell. In 1971 I was

a young, ex-monk, hippie, grad student in comparative religions, and

budding, outspoken gay activist—and a work-scholar at a

Jungian-oriented seminar center north of San Francisco, which is how I

met and befriended Joe. I continued on the team that put on his

appearances in Northern California and carried on a personal

correspondence with him through the 70s.

Gracious

and open-minded—that’s how I experienced Joseph Campbell. In 1971 I was

a young, ex-monk, hippie, grad student in comparative religions, and

budding, outspoken gay activist—and a work-scholar at a

Jungian-oriented seminar center north of San Francisco, which is how I

met and befriended Joe. I continued on the team that put on his

appearances in Northern California and carried on a personal

correspondence with him through the 70s.

Only half-jokingly, I fancy myself “Joseph

Campbell’s Apostle to the Gay Community.” His explanation of religion

saved me from my 1950s Catholic upbringing. As editor of White Crane

Journal and writer about gay men’s spirituality, I’ve touted his

perspective—from outside and over and above—as a naturally gay way to

understand religion. Such an understanding can be a positive cure for

the homophobia and confusion that traditional religion imposes on gay

and sex-variant people. My gay spirituality books are about how the

Campbellian understanding of myth as a clue to the nature and patterns

of consciousness explains the religious problems away. So I can’t help

but wonder about the exchange between Campbell and Kinsey.

An internet search on “A Dinner, a Talk, a Walk with Forster”

will bring up Wescott’s article with its couple of sly hints at the

conversation. This event did not make it into any of Campbell’s

published journals, the Director of the Campbell Foundation told me,

but those journals are now in the New York Public Library’s Joseph

Campbell Collection and are open to the public. If any G&LR reader

would peruse Joe’s journals for 1949, I think we’d all love to know

what he wrote about that evening.

Toby Johnson

Here's an interesting article about Monroe

Wheeler, published on the White Crane Institute email blasts of famous

gay birth and death dates.

Feb 13, 1899 - 1988

MONROE

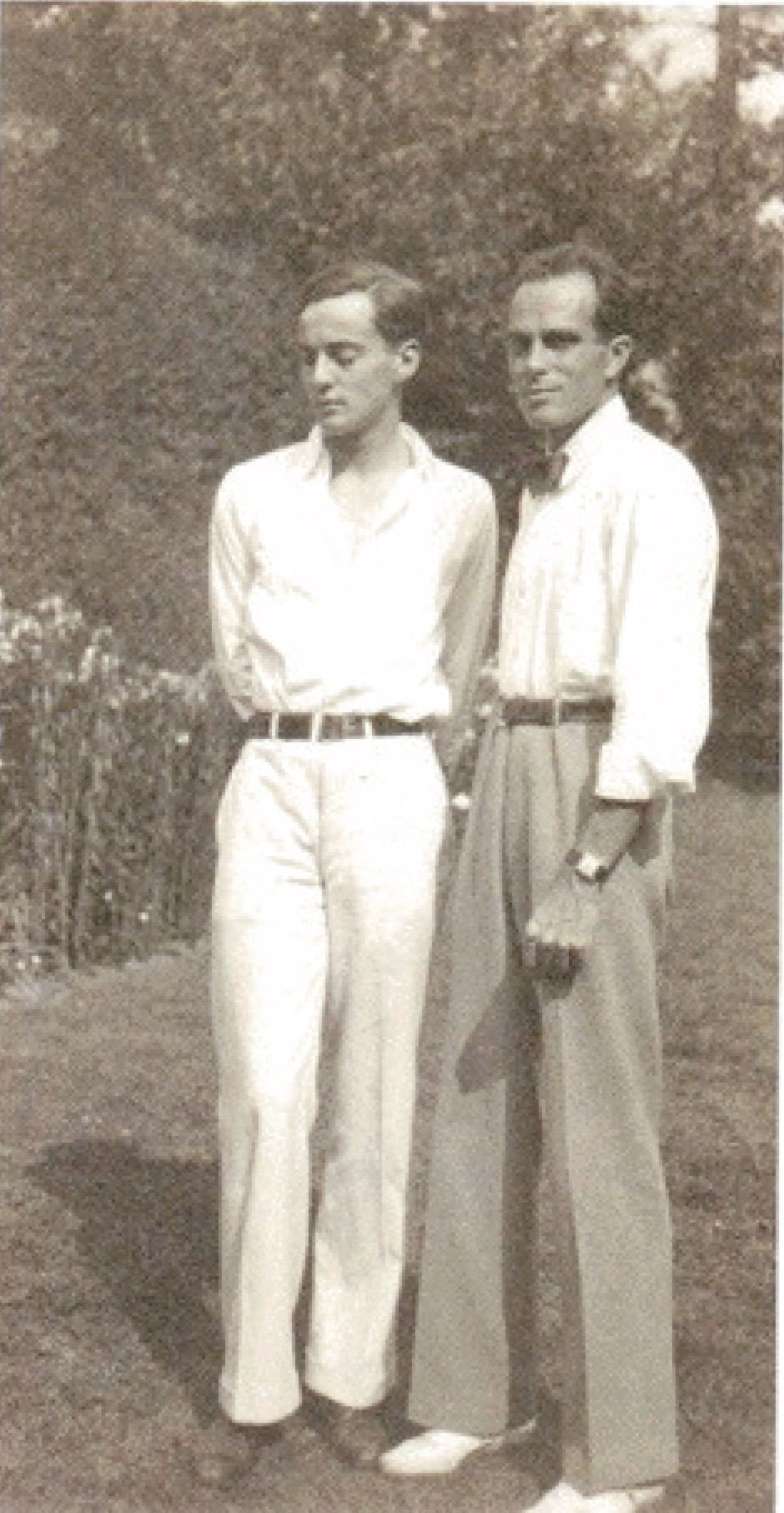

WHEELER, American curator, born (d: 1988); Poet and author Glenway

Wescott and Monroe Wheeler were an extraordinary couple. The two met

for the first time in 1919, and it was, it seems, a classic case of

love at first sight. At the time, Wescott was still in his teens and

Wheeler just 20. (Wescott's photo below) Seemingly inured to the social

mores of the time and inconstancies of youth, the two embarked on a

relationship that can be called nothing short of a marriage, for the

next 68 years, until Wescott's death in 1987.

MONROE

WHEELER, American curator, born (d: 1988); Poet and author Glenway

Wescott and Monroe Wheeler were an extraordinary couple. The two met

for the first time in 1919, and it was, it seems, a classic case of

love at first sight. At the time, Wescott was still in his teens and

Wheeler just 20. (Wescott's photo below) Seemingly inured to the social

mores of the time and inconstancies of youth, the two embarked on a

relationship that can be called nothing short of a marriage, for the

next 68 years, until Wescott's death in 1987.

The

young couple traveled the world, stopping in on Gertrude Stein's Paris

Salon and crossing paths with Jean Cocteau on the Riviera, while

Wescott developed his poetry and later fiction (he authored The

Grandmothers and The Pilgrim Hawk, among other bestsellers of his day)

and Wheeler found his path. Eventually he would become the director of

exhibitions and publications at the Museum of Modern Art.

The

young couple traveled the world, stopping in on Gertrude Stein's Paris

Salon and crossing paths with Jean Cocteau on the Riviera, while

Wescott developed his poetry and later fiction (he authored The

Grandmothers and The Pilgrim Hawk, among other bestsellers of his day)

and Wheeler found his path. Eventually he would become the director of

exhibitions and publications at the Museum of Modern Art.

The

two moved with equal ease through the literary and artistic circles of

London and the continent as well as their families' Midwestern homes.

That their relationship thrived is notable enough. But 1927 brought a

new challenge to their pairing. High-school student George Platt Lynes

fell passionately in love with the strikingly good-looking Wheeler. And

Wheeler, for his part, was entranced by Lyne’s 'full, luscious mouth

and his wasp-like waist'. Instead of driving a wedge between Wescott

and Wheeler, as might be expected, Lynes soon became part of their

shared life. When, after some casting about, he hit upon photography,

the two nurtured his career and used their considerable connections to

get him both work and gallery shows.

The

two moved with equal ease through the literary and artistic circles of

London and the continent as well as their families' Midwestern homes.

That their relationship thrived is notable enough. But 1927 brought a

new challenge to their pairing. High-school student George Platt Lynes

fell passionately in love with the strikingly good-looking Wheeler. And

Wheeler, for his part, was entranced by Lyne’s 'full, luscious mouth

and his wasp-like waist'. Instead of driving a wedge between Wescott

and Wheeler, as might be expected, Lynes soon became part of their

shared life. When, after some casting about, he hit upon photography,

the two nurtured his career and used their considerable connections to

get him both work and gallery shows.

In 1930, while still in France, Wheeler entered

into a partnership with Barbara Harrison to establish the Harrison of

Paris press, the goal of which was to publish fine editions of new and

neglected classics. Over 5 years, they produced 13 titles, including

works by Thomas Mann, Katherine Anne Porter, and Glenway Wescott's A

Calendar of Saints for Unbelievers, with illustrations by Pavel

Tchelitchev.

In 1935, following the marriage of Barbara

Harrison to Glenway's younger brother, Lloyd, Wheeler and Wescott moved

back to the United States. They soon set up households both on the farm

in New Jersey bought by Barbara Harrison and Lloyd Wescott and in New

York City, where they shared a series of apartments with George Platt

Lynes.

It was at this time that Wheeler began an

association with the Museum of Modern Art when, in 1935, he

guest-curated an exhibit. His position at MOMA became permanent in 1938

when he was hired as Membership Director, then moved quickly into the

position of Director of Exhibitions and Publications. Wheeler's

innovations in publication and exhibit design soon became well-known.

In 1951, in recognition of his work in bringing French artists to the

attention of American viewers, he was made a Chevalier of the French

Legion of Honor by the government of France.

In 1967, in preparation for his retirement, Wheeler shifted his duties

at the museum. Having long been a trustee of the museum, he was

appointed counselor and joined the International Council in its

biannual meetings. After his official retirement in 1967, he continued

to advise the museum on exhibitions and serve with a number of civic

and arts organizations.

In 1969, Wheeler traveled as a cultural advisor with Nelson Rockefeller

on a presidential mission to Latin America. In the 1970s, Wheeler

travelled extensively and worked on projects documenting the history of

MOMA and the collections of the Rockefeller family.

Monroe Wheeler died in Manhattan on August 14th 1988 at the age of 89, 18 months after the death of Glenway Wescott.

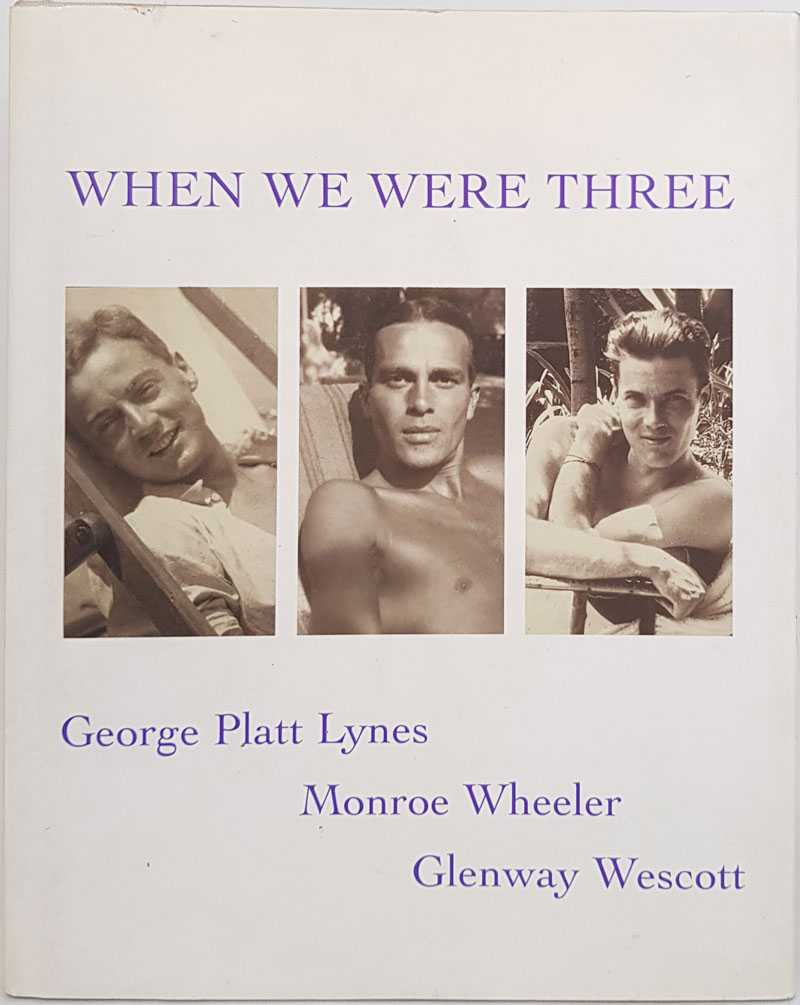

The relationship of Lynes, Wescott and Wheeler was celebrated in a book titled: When We Were Three: The Travel Albums of George Platt Lynes, Monroe Wheeler, and Glenway Wescott, 1925-1935

Here's the cover:

Letter to the Editor:

Letter to the Editor: Letter to the Editor:

Letter to the Editor:![]()