One of the Strangest Events in my Life

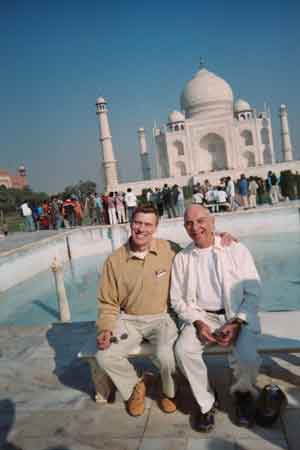

In November 2006, Kip and I went on a tour with

Gate 1 Travel of Northern India—the "Golden Triangle"— and Nepal. It

was a wonderful adventure. India is so different from America. It was

thrilling; it was scary; it was disturbing; it was great fun. All these

things are true.

We arrived in New Delhi, were shown the sights

there, then driven by small motor coach to Jaipur, the "Pink City,"

then Agra to see the Taj Mahal.

Then we got on a train and traveled to Khajuraho

to see the Erotic Temple complex. Then we flew to Varanasi, the

birthplace of Buddhism, and site of the famous burning ghats along the

Ganges where faithful Hindus hope to be cremated after their deaths and

their remains and ashes cast into the sacred river.

Then we boarded another plane and flew to

Kathmandu, where we got to fly in a small plane--on an airline called

Buddha Air--up to Mount Everest. The plane flew along the front range

of the Himalayas. After a couple of days in Nepal, we flew back to New

Delhi and then back to the United States.

A marvelous trip. More tourism than sacred

pilgrimage. Kip joked he'd hoped to experience India like Beatle George

Harrison amd come home spiritually transformed. But that isn't really

what happened. It was more frightening and disquieting than it was

"spiritual"—so much suffering. Beggars everywhere. Children pulling at

our clothes trying to sell us trinkets or to give them alms. Everywhere

crowds. Everywhere animals and cars and trucks and motorcycles and

motorized rickshaws called tuck-tucks. It was overwhelming, though

exciting.

Because of my interest in Buddhism which I learned

from reading Alan Watts and Joseph Campbell, I was especially looking

forward to seeing Varanasi, the city that used to be called Benares,

where the Buddha gave his first sermon in Deer Park. And indeed the

tour guide took us to Deer Park and we saw--and

circumambulated--Buddha's Stupa. We arrived late in the day and the

museum and park were closing, so our visit was rushed.

We'd flown into the Varanasi airport, and were taken to

the hotel first to check in and wash up before starting the tour of the Buddhist sites. The

hotel was a new-looking building, very modern, very American, with the

international-sounding name Radisson Varanasi.

Kip and I were assigned a room with two twin beds

on one of the higher floors. We had quite a view out the window—though

it was of a dilapidated city. And—which the photos do not show—there

were swarms of buzzards flying round and round over the cityscape.

The room was beautifully appointed, with ancient-looking art on the walls and lovely modern furniture.

We were appropriately tired from a long day, November 29, 2006. And went to bed soon after we got in for the evening.

I was awakened after a little while by the small of smoke. We'd seen

the guest across the hall from us had arrived while we were still

getting settled and had the door open. He'd been smoking a cigar. I

thought that was the source of the smell.

But then the smell got stronger. I remember thinking,

half-asleep and a little paranoid, that maybe the man had seen that

we'd been offended by his cigar and was, in retaliation, blowing his

smoke directly under our door.

That didn't make much sense, but why such a strong smoke smell? I lay

awake wondering what to do. Kip seemed to be sleeping soundly in the

other bed, but I worried that one of us should stay awake just in case…

Finally I woke him to ask if he smelled smoke too. Yes, of course, he

did. It was very pronounced. And it wasn't cigar smoke. We called down

to the front desk to report. At first they said it was nothing. There'd

been no report of a fire in the hotel. We were just imagining it.

Well, it is true that India smells of burning cow dung and marijuana

smoke virtually everywhere. But this was so much stronger. We tried to

go back to sleep, but I was not satisfied. If there were a fire in the

hotel, somebody needed to know. We called down to the front desk and

asked them to have somebody come up to the room and smell what we were

smelling. Reluctantly, they agreed. And shortly a fellow in a

military-looking, security-guard uniform came to the door. He walked

in, sniffed around, then said he didn't smell anything unusual.

By that time, the smoke had gotten thick enough that it was billowing

in the room. Kip pointed to a little niche with a lamp that stood on

the minibar. You could see smoke swirling in the niche. "What's that,

then?"

The bellman looked intently and then replied, "That's a lamp." Well, we

were getting nowhere. He left, but promised to pay attention in case

there really had been smoke somewhere.

Nothing was changing and we couldn't go back to sleep. Somebody had to do something. So we went downstairs in the elevator and

to the front desk and asked to speak to the manager. We stood in the

lobby (shown in the photo with people in it; in the middle of the night

it was empty) and tried to explain what we thought was happening.

Somebody had to do something. So we went downstairs in the elevator and

to the front desk and asked to speak to the manager. We stood in the

lobby (shown in the photo with people in it; in the middle of the night

it was empty) and tried to explain what we thought was happening.

The manager was a young Indian man, very polite, but very officious. He

assured us there was no fire. No else had reported smelling smoke. And,

besides, he said, he only stays at the hotel on certain nights of the

week. Tuesday was one of his days. "And since I am here," he said,

"there could be no fire. I am here tonight."

That logic wasn't very reassuring, though quoting him has become a joke

between Kip and me about how oblivious people can be when they just

might be wrong.

We went back to the room and tried to go back to sleep. I found myself

caught in this Great Worry and feeling of responsibility—for Kip,

certainly, and our lives together, but also for the other guests in the

hotel. I tried to rest, but had to keep myself from falling asleep.

I don't remember clearly how all this came down. But I think I finally

got up and went back to the lobby by myself to insist that there was

smoke in our room. And this time the manager was more forthcoming. He

told me that they had installed a new woodburning cookstove in the

kitchen and in trying it out had overloaded it. There really had been

smoke. And, he said, our room at the end of the hall was next to a

stairwell that came up directly from the kitchen. Other people weren't

complaining because it was only at the end of one hall.

So problem resolved.

But what was that about?

It was only much later that I put that experience together with what I

knew to be a meditative practice and ritual among Mahayana and Tibetan

Buddhists called Tonglen. It was something I'd run across and practiced

myself off and on a little out of my fascination with the myth of the

Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara who takes upon himself the suffering of the

world in order to transform it by his insight that ego doesn't really

exist.

Here's a description of performing tonglen

Imagine

the sorrows and sufferings of the world

as dark smoke, perhaps like smoke from incense, or fumes from a blown

out candle. Imagine the smoke filling the room. Breathe in the smoke.

Relax and be aware of your breath, and be aware of breathing in the

black smoke, so that the mental space inside your body becomes dark and

choked with the smoke. Keep breathing it in till the inside of the

space in your body is as dark as night.

Then visualize a lightning

flash – the

lightning bolt of enlightenment: vajra.

The vajra scepter is the stylized

solidification

of a lightning bolt. Tibetans thought when lightning struck the ground

it congealed into a diamond. So the vajra is both lightning bolt and

diamond – both images of enlightened mind.

In the

bright flash

of the lightning--cutting through the darkness and cutting through time

to illuminate an eternal moment--let yourself visualize the smoke and

darkness changing to bright colorful lights, like flowers in spring or

like the flashing of sunlight off the surface of water, shimmering and

beautiful, warm and relaxing.

Breathe in the

smoke

and darkness of human sorrow and suffering in the transitoriness of

time, let it be transformed in the lightning bolt striking into your

heart and congealing into a diamond, and let it become joy for life and

bliss in the eternity of consciousness transcending individuality.

Breathe in smoke,

breathe out joy. That's what a bodhisattva does, using skillful means

to say just the right thing or make the right gesture to soothe

suffering, "participating joyfully in the sorrows of the world."

Well, what better place on Earth to

experience tonglen than in Varanasi, India? And I wasn't doing it; it

was being done unto me. Some "power" so much bigger than my little ego

was reminding me of how little my ego is by doing it to me.

I didn't realize how that crazy

experience with the overly-confident and officious hotel manager and

the overloaded new cookstove was a dramatization of the tonglen ritual

till years later. I've wondered what it means that it took me so long.

And did I do it correctly? Did I get the lesson? I'm not sure.

In the morning, we joked with the other

people on the tour about our experience. One other couple had noticed

the smoke, but hadn't said anything. At least, it was real. We'd gotten

up very early to go to the Ganges to watch the sunrise. And were taken

out into the pitch dark city by bus to near the burning/burial ghats.

We had brought with us a small portion of the ashes of our friend Cliff Douglas who'd died some 10 years before, and scattered them in the sacred water as the sun was rising.

There

were vendors selling candles in folded palm leaves to float on the

water. We bought one of those, and from a little boat our tour guide

had arranged for us, we placed the candle on the river and then Kip

poured out the ashes.

There

were vendors selling candles in folded palm leaves to float on the

water. We bought one of those, and from a little boat our tour guide

had arranged for us, we placed the candle on the river and then Kip

poured out the ashes.

As we watched, the sun rose on the other side of the river.

As we watched, the sun rose on the other side of the river.

It was magical bringing our friend's ashes to the Holy Ganges.

I

have wondered what that smoke in the hotel room meant in my life. Was

there a "message" from the universe in that? Was it acceptance—or

rejection—of my intentions to be responsible?

I'd just turned 61 the August before that November trip to India. I

have to say I think I started aging soon after we returned. I began to

experience the benign prostate hypertrophy which is so common in men as

we outlive the reproductive years.

The "Four Signs" that called Prince Gautama to leave the palace and

seek Buddhahood were the sight of an old man, a sick man, a dead body,

and a monk. Maybe that's what's in the smoke of tonglen: the reality of

age, disease, and death.

What choice do we have but to accept this gracefully, as the reality

we're in, and to breathe deeply, transforming the smoke—but then

alerting the authorities?

Read Toby's suggestion for funeral practices that embody the Tonglen imagery.

Read an excerpt from The Fourth Quill about the nature of suffering: The Closet of Horrors

In Volume 13

of his collected works Jung quotes a letter from one of his patients

which he says articulates the essential lesson—that seems to express

the Bodhisattva attitude we must strive to adopt.

“Out of evil, much

good has come to me. By keeping quiet, repressing nothing, remaining

attentive, and by accepting reality – taking things as they are, and

not as I wanted them to be – by doing all this, unusual knowledge has

come to me, and unusual powers as well, such as I could never have

imagined before. I always thought that when we accepted things they

overpowered us in some way or other. This turns out not to be true at

all, and it is only by accepting them that one can assume an attitude

towards them.

"So now I intend to play the game of life, being

receptive to whatever comes to me, good and bad, sun and shadow forever

alternating, and, in this way, also accepting my own nature with its

positive and negative sides. Thus everything becomes more alive to me.

What a fool I was! How I tried to force everything to go according to

way I thought it ought to."

— Carl Jung, Alchemical Studies, p 47

![]()